Fiber in IBD

Why Fiber Matters and How to Add it Safely

For many years, people living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were often told to avoid high-fiber foods out of concern that they might worsen symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain, or diarrhea.

However, research over the past decade has transformed how we understand the role of fiber in IBD. Instead of being a universal “trigger,” fiber is now recognized as a vital component of gut health, with the potential to reduce inflammation, nourish the gut microbiome, and improve quality of life.

This page explores what science tells us about fiber and IBD, practical ways to adapt fiber intake during flares and remission, and how small, gradual dietary changes can help people with IBD move toward more balanced and protective eating patterns.

.webp)

From "Low-Fiber" to "Incorporate Fiber"

Decades of research have shown that fiber-rich diets provide benefits for gut health, cardiovascular health, and cancer prevention. The recommendation for fiber intake ranges from 19 to 38 g/day for children, and from 25 to 38 g/day for healthy adults, while most American adults eat 10-15 grams of fiber per day.1 However, patients living with IBD have had difficulty meeting these targets because of the fear that it may aggravate loose stool, bloating, abdominal pain, and gas.

During the last decade, there has been a shift in dietary fiber advice for IBD from “follow a low-fiber diet” to “how you can incorporate fiber in a way that does not increase symptoms”.2-4

This is based on new research suggesting that a low-fiber diet is not necessarily the best choice for IBD management. Poor food-related quality of life in IBD, especially in flares and ongoing disease, is associated with eating less fiber.5 In addition, patients with IBD in remission can tolerate healthy diets with adequate dietary fiber (25-35 g/day).6-8

Here are four important topics about the role of fiber in IBD:

1. Not All Fibers Work the Same

Dietary fiber is a type of carbohydrate that our digestive systems cannot break down, and it can impact the digestive tract and health in different ways depending on the type of fiber it is. The main characteristics of fiber that affect its function in the body are:4,9,10

Solubility - How well does fiber dissolve in water

- Insoluble fiber

- Stimulates intestinal contractions

- Triggers mucus secretion

- Adds bulk to the stool

- It passes through the intestines almost intact (like a street sweeper)

- Helpful for constipation

- Soluble fiber

- Slows down digestion

- Pulls water from stool

- Forms a gel during digestion and softens the stool (like a sponge)

- Helpful for both diarrhea and constipation

Viscosity - How thick it becomes when mixed with water (gel-forming action)

- Helps to thicken the stool

- Slows the movement of food through the digestive tract

- Reduces blood sugar spikes and lowers cholesterol

Fermentability- The degree to which the gut microbiota can ferment it

- Bacteria generally ferment soluble fibers in the lower intestine

- Insoluble fibers are generally less fermentable by gut microbiota (fermentability of insoluble fiber varies, from none/low to moderate)

💡 It’s important to remember that, like many aspects of nutrition in IBD, the impact of fiber can vary from person to person and may shift depending on disease activity and the fermentative capacity of the gut microbiota.

What works well during remission might not be tolerated during a flare, and vice versa. This means that a particular food rich in fiber may be poorly tolerated now, but in a few months, the person with IBD may be able to eat it again without issues.

2. Why Fiber is Crucial in IBD

Fiber has the potential to modify the course and complications of IBD through its strong influence on the gut microbiome composition and metabolites (the substances the microbiota produce).

Fiber has been associated with the following benefits in IBD:

- increased production of short-chain fatty acids with anti-inflammatory properties

- decreased incidence of flares

- increased the length of time between flares

- decreased incidence of pouchitis in ulcerative colitis

- Fiber nourishes the microorganisms growing and living in the colon, which can have a protective role in IBD11

- Eating fiber from a variety of sources promotes a diversity of microbes, which has the potential to lower inflammation12

- Short-chain fatty acids (acetate, butyrate, and propionate) are metabolites generated by gut microbes in people who consume a fiber-rich diet that11:

- Have anti-inflammatory properties

- Aid in fluid and electrolyte absorption

- Serve as the colon’s primary fuel source

In contrast, in individuals with inadequate fiber intake, gut microbes will break down the protective mucus that lines intestinal cells.

As a result, the protective mucus layer of the intestine becomes thinner, allowing pathogens to cross the gut barrier and trigger an inflammatory response13

3. How to Choose the Right Fiber Type and Texture in IBD

Patients with IBD may be sensitive to dietary fiber. However, available and mounting evidence suggests that instead of recommending a low-fiber diet in IBD, it is essential to try different types of fiber to see what works for you. Tolerance is very individual.

Below are four situations that patients may face, along with tips for incorporating fiber in each scenario.

Patients with diarrhea as the predominant bowel symptom

💡 Increase soluble, gel-forming fibers based on individual tolerance and preference14

- Potato

- Sweet potato

- Turnips

- Avocado

- Carrots

- Peas

- Citrus fruits

- Bananas

- Applesauce

- Berries

- Pears

- Oats

- Beans (e.g., hummus or bean puree)

- Psyllium husk*: soluble, viscous, low fermentable fiber that does not worsen gastrointestinal symptoms

*This fiber can be added to your smoothies, overnight breakfast chia bowl, homemade sourdough bread, or baked into your favourite recipes.

💡 Psyllium husk is a soluble, viscous, low fermentable fiber. Patients with diarrhea, constipation, or fecal incontinence might benefit from fiber found in psyllium.

Patients with constipation as the predominant bowel symptom

💡 Increase insoluble fibers that add bulk to the stool17,18:

- Whole wheat flour

- Wheat or oat bran

- Vegetable/fruits/legume peels/shells (e.g., cauliflower, green beans)

- Nuts

- Seeds

💡 Higher frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption is associated with greater daily stool weight. Particular foods and food supplements that may keep constipation at bay are19-23:

- 2 tablespoons/day of flaxseed

- 2 kiwifruits per day

- Rye bread

- Prunes

- High-mineral water

- Psyllium*

- Some probiotics

- Kiwifruit supplements

*If you are using a fiber supplement, we recommend starting with 2-3 grams daily (½ teaspoon), divided into two doses, and gradually increasing at one- to two-week intervals up to 10-12 grams daily.

💡 In patients who do not respond to increased dietary fiber, water, and exercise, it is worth exploring if the root involves a disordered bowel habit (inability to coordinate the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles to evacuate stools)2

Patients with UC who have undergone total colectomy and J-pouch surgery

💡 May benefit from:16

- Including soluble, gel-forming fibers, like psyllium, which may help to slow gastric emptying, thicken stools, and support the microbiome

- Limiting insoluble fiber (wheat or oat bran, vegetable/legume peels, nuts, and seeds), which may increase the frequency of bowel movements and cause watery stool

💡 The consumption of at least one and a half fruit servings daily may reduce the risk of developing pouchitis by increasing gut microbiota diversity15

Individuals with increased gas, bloating, and flatulence

💡 Decrease fermentable fibers:16,17

- Beans

- Wheat dextrin

- Oligosaccharides: fructans (e.g., inulin found in wheat, onions, leeks, artichokes, asparagus, and added as chicory root extract to foods and supplements) and galacto-oligosaccharides (e.g., legumes, pistachios, cashews)

💡 Increase intake of oats, flaxseeds, or chia seeds

Tips for Building Fiber Tolerance

To better tolerate dietary fiber, it is essential to gradually increase fiber intake over 1-2 weeks and drink plenty of water (this applies to all types of fiber). Small swaps or additions can have a big impact. For example, you can try:

- Incorporating 1 tbsp of chia seeds as a snack or dessert, which increases fiber by 5 grams.

- Swapping regular pasta with whole-wheat pasta: start by using a 1:1 ratio (half regular, half whole-wheat); if tolerated, you can increase the whole-wheat content and decrease the white pasta content.

- Adding 1 TBSP of cooked legumes to salads or dishes and working your way up to ½ cup serving.

4. Fiber and IBD-related complications

Patients with IBD-related complications are more likely to avoid fiber-rich foods. One important aspect to bear in mind is that fiber texture and digestibility matter more than fiber content. So instead of focusing on "low fiber", it is more important to think in terms of low roughage. Even a food low in fiber (e.g., rubbery steak) can still pose a risk for obstruction.

Rule of thumb: If the food, regardless of fiber content, is fork-tender, it might be safe to consume.

For patients with strictures, adhesions, obstructive symptoms, active disease (inflammation), or sensitivity to whole foods25:

- A soft-texture diet may be recommended to ease digestion and minimize discomfort.

- Opt for cooked, peeled, or blended versions of fruits and vegetables

- Avoid high-fiber, hard-to-digest items like raw nuts or raw legumes

- Fiber content of a food is not the only factor to consider: despite being low in fiber, some meats are rubbery or plain hard to break down and pose a risk for obstruction

- Consider adding nutritious fluids (e.g., nutrition shakes) to achieve hydration goals and meet calorie needs (inflammation just up energy and protein needs)

- Stay hydrated, chewing well, eating slowly, watching portions, and maintaining good posture during and after meals also help reduce the risk of obstruction

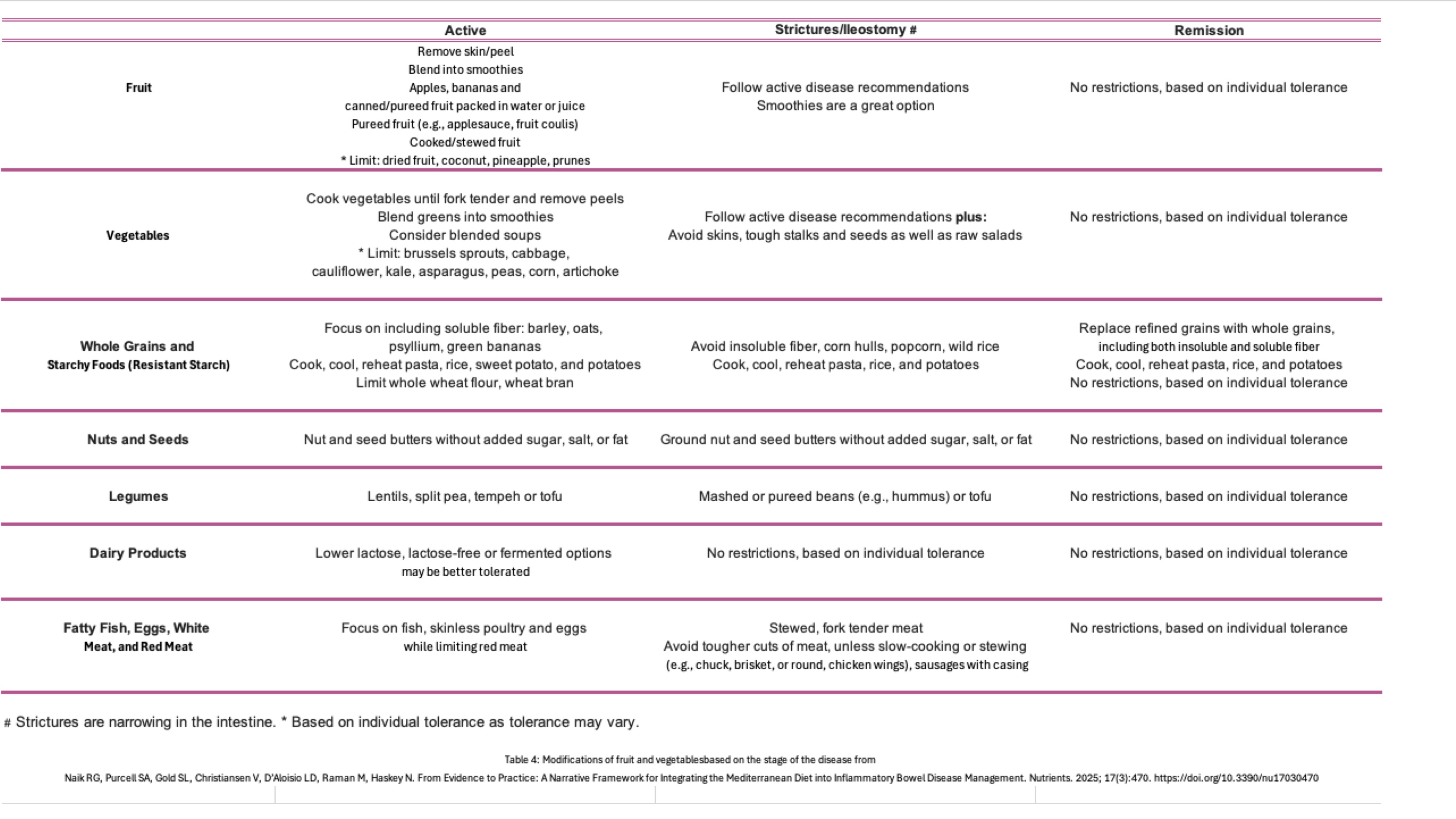

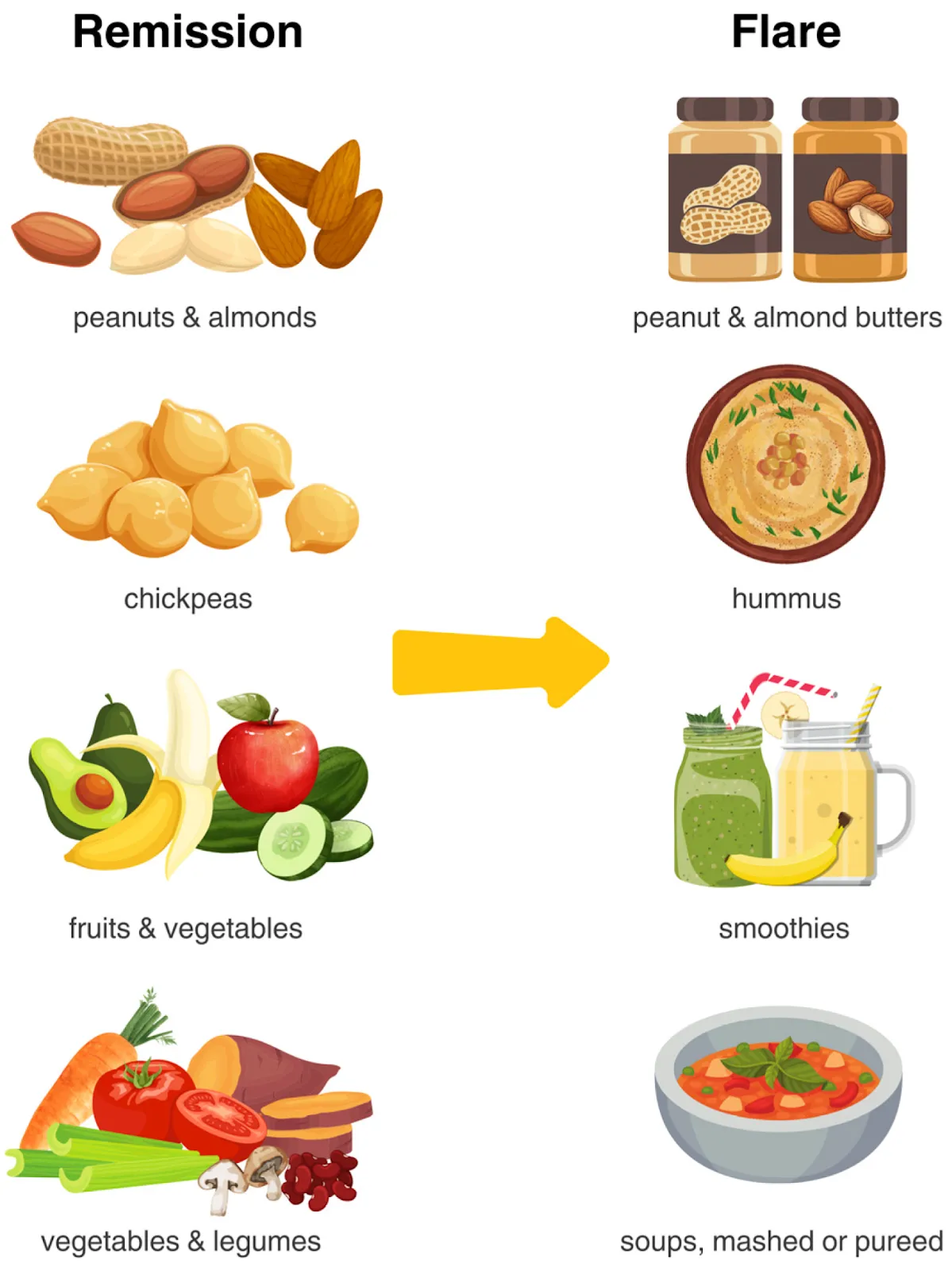

Modifications of fruit and vegetables based on the stage of disease25

During remission (as long as the patient is not at risk for obstruction due to scar tissue):

- Patients can focus on gradually consuming nutrient-dense, whole foods as tolerated:

- Nuts

- Legumes

- Whole fruit

- Whole or uncooked vegetables

- Slowly adapt your diet to make it more Mediterranean diet-like with whole foods, pick one change every week, and incorporate it gradually

Explore our recipe page for foods specifically appropriate for IBD.

Here are some examples of high-fiber, soft-texture recipes

- Fiber is no longer universally restricted in IBD

- The old advice of avoiding fiber is shifting to a more personalized approach.

- Patients in remission can often tolerate and benefit from a fiber-rich diet.

- Fiber intake in IBD is often too low

- General recommendations for adults: 25–38 g/day.

- Most people with IBD eat much less due to symptom concerns (bloating, gas, diarrhea, pain).

- Not all fibers act the same

- Insoluble fiber: adds bulk, stimulates movement, helpful for constipation.

- Soluble fiber: forms gel, stabilizes stool consistency, helpful for both diarrhea and constipation.

- Viscous fibers: thicken stools, slow digestion, help blood sugar and cholesterol.

- Fermentable fibers: feed gut microbes, producing short-chain fatty acids with anti-inflammatory effects.

- Fiber benefits for IBD

- Supports a healthier gut microbiome.

- Produces anti-inflammatory compounds (short-chain fatty acids).

- May reduce risk and frequency of flares.

- Increases time in remission.

- Lowers risk of pouchitis in ulcerative colitis.

- Tolerance varies with disease activity

- Foods may be poorly tolerated during a flare but well tolerated during remission.

- Fiber tolerance depends on the type, texture, and individual microbiome.

- Practical dietary strategies

- Increase fiber gradually and drink enough water.

- Make small swaps (whole grains for refined, add legumes in small amounts, use chia/flax/psyllium).

- Adjust fiber type depending on symptoms:

- Diarrhea → more soluble, gel-forming fibers (e.g., oats, bananas, psyllium, sweet potato).

- Constipation → more insoluble fibers (e.g., whole grains, bran, peels, seeds).

- Gas/bloating → lower fermentable fibers (e.g., reduce beans, onions, inulin) and favor gentler fibers (e.g., oats, flax, chia).

- Fiber and complications

- Patients with strictures, adhesions, or high obstruction risk should focus on texture modification (soft, cooked, peeled, blended foods) rather than simply “low fiber.”

- Rule of thumb: “fork-tender” foods are typically safer.

- Mediterranean-style eating as a long-term goal

- Over time, patients (in remission, without strictures) can move toward a Mediterranean diet pattern rich in whole foods, fruits, vegetables, legumes, seeds, and nuts, introduced gradually.

- Individualization is key

- Fiber needs and tolerances differ by person and by stage of IBD.

- Continuous adjustment, gradual changes, and professional dietitian guidance are recommended.

Bottom line: Fiber is not the enemy in IBD, it is an essential tool for gut health when chosen carefully. The focus should shift from restriction to personalized inclusion, adapting the type, texture, and timing of fiber to symptom patterns and disease activity.

It is always advisable to consult a healthcare provider or a registered dietitian for personalized recommendations tailored to your unique needs. Remember, everyone's experience with IBD is unique, and finding the right foods for your body is central to managing this condition effectively.

Author: Andreu Prados, PhD, RD, BPharm,

Medical Reviewers: Natasha Haskey, PhD, RD, and Colleen Webb, MS, RDN

References

- Institute of Medicine: Dietary, functional, and total fiber. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy,Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol,Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients).Washington, DC: National Academies Press,2005; pp 339 – 421.

- Bischoff SC, Bager P, Escher J, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2023; 42(3):352-379. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2022.12.004.

- Chan LN (editor-in-chief). ASPEN Adult Nutrition Support Core Curriculum. 4th edition. 2025. ISBN: 978-1-889622-58-3.

- Haskey N, Gold SL, Faith JJ, et al. To fiber or not to fiber in IBD: the swinging pendulum of fiber supplementation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients. 2023; 15(5):1080. doi: 10.3390/nu15051080.

- Whelan K, Murrells T, Morgan M, et al. Food-related quality of life is impaired in inflammatory bowel disease and associated with reduced intake of key nutrients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021; 113(4):832-844. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa395.

- Fritsch J, Garces L, Quintero MA, et al. Low-fat, high-fiber diet reduces markers of inflammation and dysbiosis and improves quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 19(6):1189-1199.e30. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.026.

- Mortera SL, Marzano V, Rapisarda F, et al. Metaproteomics reveals diet-induced changes in gut microbiome function according to Crohn’s disease location. Microbiome. 2024;12:217. doi: 10.1186/s40168-024-01927-5.

- Haskey N, Estaki M, Ye J, et al. A Mediterranean diet pattern improves intestinal inflammation concomitant with reshaping of the bacteriome in ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2023; 17(10):1569-1578. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad073.

- Gill SK, Rossi M, Bajka B, et al. Dietary fibre in gastrointestinal health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 18(2):101-116. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00375-4.

- So D, Gibson PR, Muir JG, et al. Dietary fibers and IBS: translating functional characteristics to clinical value in the era of personalised medicine. Gut. 2021; 70(12):2383-2394. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324891.

- Fusco W, Bernabeu Lorenzo M, Cintoni M, et al. Short-chain fatty-acid-producing bacteria: key components of the human gut microbiota. Nutrients. 2023; 15(9):2211. doi: 10.3390/nu15092211.

- Wastyk HC, Fragiadakis GK, Perelman D, et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell. 2021; 184(16):4137-4153.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.019.

- Prados-Bo A. A fiber-deprived diet may degrade the colonic mucus barrier and promote enteric pathogen infection in mice. Gut Microbiota for Health. December 18th, 2016. Available on: https://www.gutmicrobiotaforhealth.com/fibre-deprived-diet-may-degrade-colonic-mucus-barrier-promote-enteric-pathogen-infection-mice/

- McKeown NM, Fahey Jr GC, Slavin J, et al. Fibre intake for optimal health: how can healthcare professionals support people to reach dietary recommendations? BMJ. 2022; 378:e054370. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2020-054370.

- Godny L, Maharshak N, Reshef L, et al. Fruit consumption is associated with alterations in microbial composition and lower rates of pouchitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2019; 13(10):1265-1272. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz053.

- Wall E. Nutrition therapies for patients with an ileoanal pouch: a moving target? Practical Gastro. 2024; 48(4). Available on: https://practicalgastro.com/2024/07/19/nutrition-therapies-for-patients-with-an-ileoanal-pouch-a-moving-target/

- Singh P, Tuck C, Gibson PR, et al. The role of food in the treatment of bowel disorders: focus on irritable bowel syndrome and functional constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022; 117(6):947-957. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001767.

- Van der Schoot A, Drysdale C, Whelan K, et al. The effect of fiber supplementation on chronic constipation in adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022; 116(4):953-969. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac184.

- Gearry R, Fukudo S, Barbara G, et al. Consumption of 2 green kiwifruits daily improves constipation and abdominal comfort-results of an international multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023; 118(6):1058-1068. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002124.

- Ramkumar D, Rao SSC. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005; 100(4):936-971. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40925.x.

- Van der Schoot A, Helander C, Whelan K, et al. Probiotics and synbiotics in chronic constipation in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr. 2022; 41(12):2759-2777. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2022.10.015.

- Van der Schoot A, Creedon A, Whelan K, et al. The effect of food, vitamin, or mineral supplements on chronic constipation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023; 35(11):e14613. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14613.

- Van der Schoot A, Katsirma Z, Whelan K, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Foods, drinks and diets and their effect on chronic constipation in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024; 59(2):157-174. doi: 10.1111/apt.17782.

- International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders (IFFGD). Expert Video: What are the latest advances in the treatment of dyssynergic defecation? Available on: https://www.youandconstipation.org/en-cnstp/view/m402-e406-what-are-the-latest-advances-in-the-treatment-of-dyssynergic-defecation-expert-video

- Gautam Naik R, Purcell SA, Gold SL, et al. From evidence to practice: a narrative framework for integrating the Mediterranean diet into inflammatory bowel disease management. Nutrients. 2025; 17(3):470. doi: 10.3390/nu17030470.

Do You Find Our Resources Helpful? Become Part of Our Community!

Subscribe to our newsletter so you get the latest news sent right to your inbox!

Donate so we can grow our outreach to the IBD Community

Get Involved as a volunteer, a fundraiser, or help us raise awareness

Donate

Donate