Fiber in IBD and IBS

Why Fiber Matters

Fiber plays an important, but often misunderstood, role in digestive health. For individuals with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), fiber tolerance depends on disease activity, gut anatomy, how quickly food moves through the digestive tract, and individual response.1-4

This page provides evidence-based guidance on fiber intake for people with IBD, IBS, or overlapping symptoms, outlining practical recommendations informed by clinical research.

.webp)

Rethinking Fiber in IBD and IBS

Decades of research have shown that fiber-rich diets provide benefits for gut health, cardiovascular health, and cancer prevention.

However, patients living with IBD and IBS have had difficulty meeting the recommended targets because of the fear that it may aggravate loose stool, bloating, abdominal pain, and gas.5,6

In the past, those living with IBD were advised to follow low-fiber diets.7,8 But during the last decade, there has been a shift in dietary fiber advice for IBD from:4,5,7,9

This shift is based on new research suggesting that a low-fiber diet is not necessarily the best choice for IBD management. Poor food-related quality of life in IBD, especially in flares and ongoing disease, is associated with eating less fiber.8 In addition, patients with IBD in remission can tolerate healthy diets with adequate dietary fiber (25-35 g/day).10-12

Fiber can support gut health, microbial diversity, and bowel regularity. At the same time, certain fibers may worsen symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or obstruction in specific clinical scenarios. Individualization is key.

What is Dietary Fiber?

Dietary fiber refers to carbohydrate components of plant foods that resist digestion in the small intestine and reach the colon relatively intact.4 Once in the colon, fiber influences stool consistency, gut transit, and microbial activity.

What are Fiber’s Functional Properties?

Recent research, particularly in IBS, suggests that fiber’s functional characteristics may better predict tolerance and symptom response than solubility alone.13,14

Fiber can be described by three key functional properties:

Not all fibers within these categories behave the same way. Differences in viscosity, fermentability, and particle size help explain why individuals may tolerate some fibers but not others.

This framework is especially helpful for individuals with IBS and for those with IBD in remission who experience IBS-like symptoms such as bloating, urgency, or altered bowel habits.

What are the Benefits of Fiber in IBS and IBD?

Fiber Tolerance Can Vary

Understanding fiber function can help guide dietary choices in IBS and in patients with overlapping IBD–IBS symptoms.

Fiber tolerance in IBS is highly individual. While fiber supplementation alone has limited benefit for improving overall IBS symptoms, certain fiber types are better tolerated than others.

Research suggests:16

- Insoluble, non-viscous fibers are common symptom triggers

- Soluble, viscous, and slowly fermentable fibers are more likely to improve global IBS symptoms

- Rapidly fermentable fibers may worsen gas, bloating, and abdominal pain

Fiber tolerance in IBD is strongly influenced by disease activity. Many individuals in remission can successfully incorporate fiber, while those with active inflammation or complications may require modifications.

What works well during remission might not be tolerated during a flare, and vice versa. This means that a particular food rich in fiber may be poorly tolerated now, but in a few months, the person with IBD may be able to eat it again without issues.

Tips to Add Fiber Safely

- Incorporating chia seeds as a snack or dessert

- 1 tbsp increases fiber by 5 grams.

- Swapping regular pasta with whole wheat pasta

- Start by using a 1:1 ratio (half regular, half whole-wheat). If tolerated, may increase the whole-wheat content and decrease the white pasta content.

- Adding cooked legumes to salads or dishes

- Start with 1 tbsp and increase to ½ cup serving.

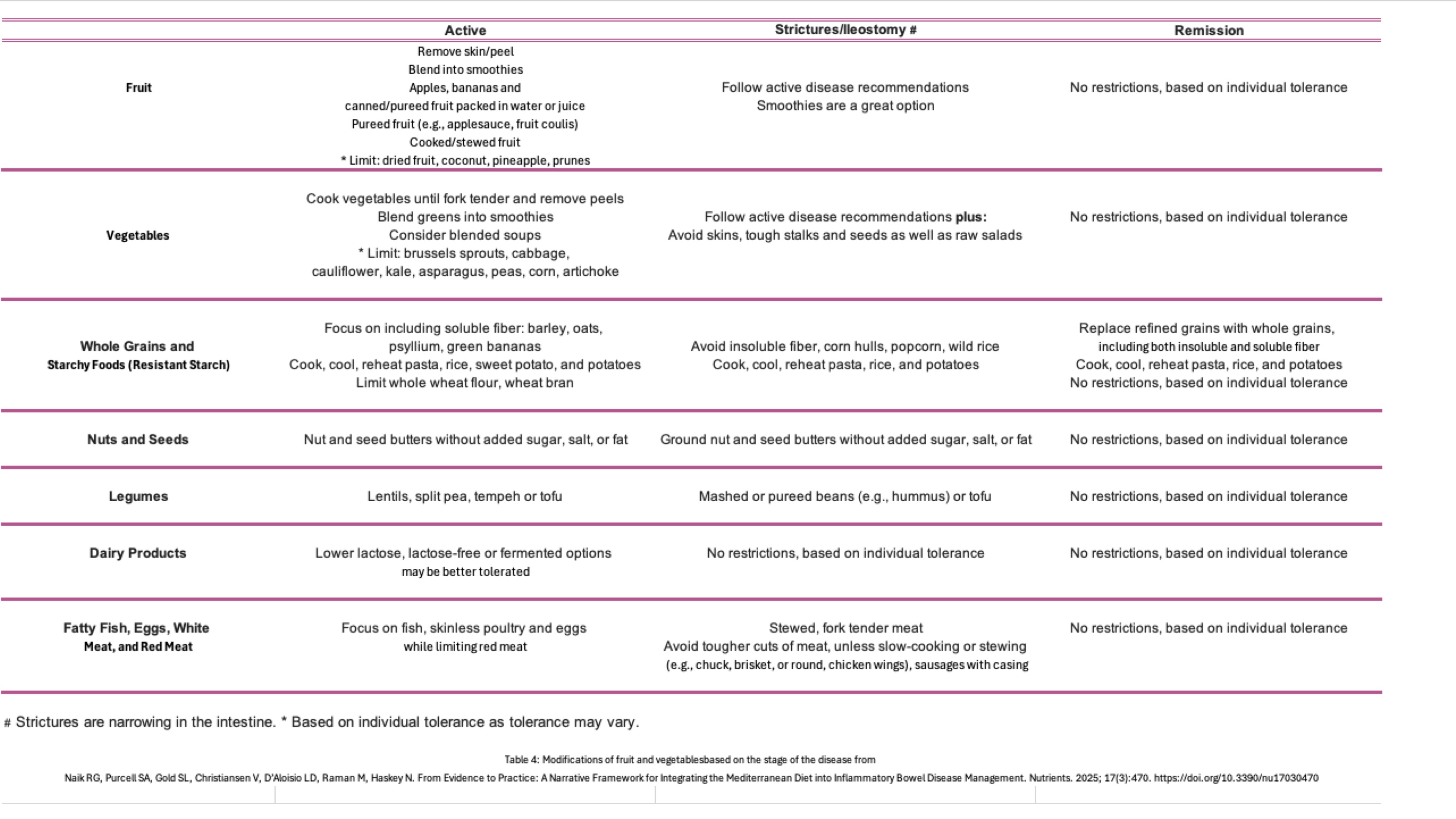

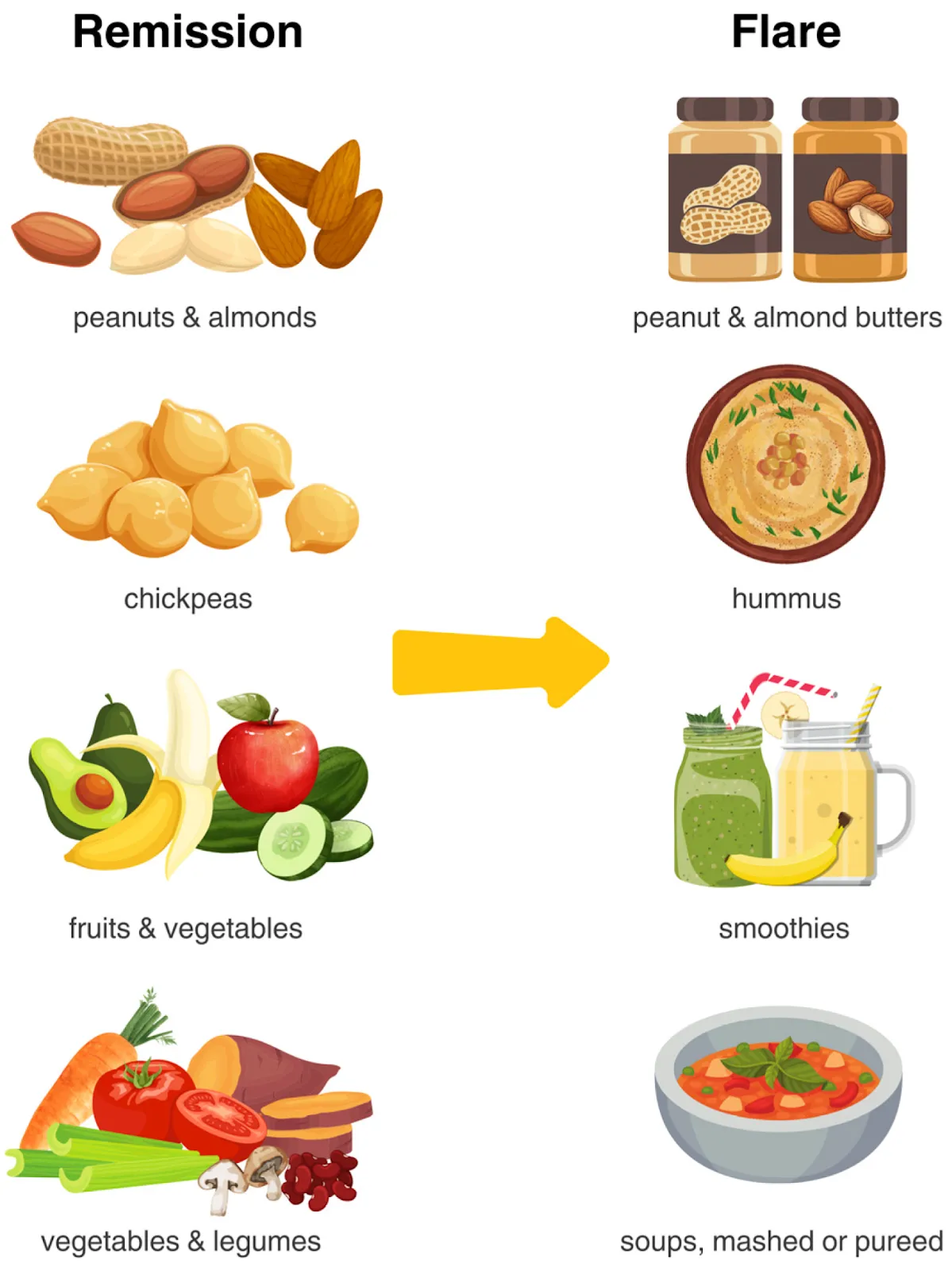

Modifications of fruit and vegetables based on the stage of disease

Choosing the Right Type of Fiber

Emerging research suggests a shift from “avoiding fiber” to “choosing the right type of fiber”.

Click the scenarios below to explore tailored recommendations and tips for different situations.

- Potato

- Sweet potato

- Turnips

- Avocado

- Carrots

- Peas

- Citrus fruits

- Bananas

- Applesauce

- Berries

- Pears

- Oats

- Beans

- Psyllium husk: a soluble, viscous, low fermentable fiber. Add it to smoothies, overnight breakfast chia bowl, homemade sourdough bread or baked into your favorite recipes.

- Pureed beans (hummus, refried pintos) instead of whole beans

- Nut butters instead of whole nuts

- Smoothie versions of fruits and veggies rich in insoluble fiber (berries, pineapple, spinach, kale)

- Whole wheat flour

- Wheat or oat bran

- Vegetable/fruits/legume peels/shells (e.g. cauliflower, green beans)

- Nuts

- Seeds

- 2 tablespoons per day of flaxseed

- 2 kiwifruits per day

- Rye bread

- Prunes

- High-mineral water

- Psyllium

- Some probiotics

- Kiwifruit supplements

*If you are using a fiber supplement, it is recommended to start with 2-3 grams per day (½ teaspoon), divided into two doses. Gradually increase at one to two week intervals up to 10-12 grams per day.

*In patients who do not respond to increased dietary fiber, water and exercise, it is worth exploring if the root involves a disordered bowel habit (inability to coordinate the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles to evacuate stools).

- Beans

- Wheat dextrin

- Certain High-FODMAP foods

- Fructans

- Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS)

- Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS)

- Fructooligosaccharides (FOS)

- Chicory fiber

- Inulin

- Lactulose

- Resistant starch

- Human milk oligosaccharides (HMO)

During an IBS or IBD flare, fiber tolerance is often reduced. Softer, well-cooked, lower-residue fiber sources may be better tolerated, while coarse or bulky fibers may worsen pain, diarrhea, or obstruction risk. Consider gentle reintroductions of plant foods in pureed, mashed, soft-cooked, or peeled forms before graduating to whole or uncooked forms.5,21

Many studies showed that in quiescent IBD healthy diets with adequate dietary fiber (>25g/day) are well tolerated. In remission, many individuals can gradually increase fiber intake. Emphasis should be placed on soluble, well-tolerated fibers to support microbial diversity and short-chain fatty acid production.10-12

During remission (as long as not at risk for obstruction due to scar tissue):

- Patients can focus on gradually consuming nutrient-dense, whole foods as tolerated:

- Nuts

- Legumes

- Whole fruit

- Whole or uncooked vegetables

- Slowly adapt your diet to make it more Mediterranean diet-like with whole foods, pick one change every week, and incorporate it gradually

In the presence of strictures or luminal narrowing, higher-risk foods such as raw vegetables, fruit skins, seeds, popcorn, and whole nuts may increase the risk of obstruction. Texture modification and individualized dietary counseling are essential.5,21

Keep in mind, fiber content of a food is not the only factor to consider. Despite being low in fiber, some foods, like meats, are rubbery and hard to break down. These foods pose a risk for obstruction.

Explore our recipe page for foods specifically appropriate for IBD.

Here are some examples of high-fiber, soft-texture recipes

After bowel surgery or in individuals with an ileostomy, fiber tolerance varies. Some fibers may increase stool output or risk of blockage, while others (e.g., soluble fibers) may help thicken stool. Gradual introduction and monitoring are recommended.

In individuals at risk for obstruction due to strictures, adhesions, or active inflammation, fiber texture is often more important than fiber quantity.5,21

- Choose soft, cooked, peeled, or blended fruits and vegetables

- Tip: Use the “fork-tender rule” — foods should be soft enough to break apart easily with a fork.

- Avoid large particle sizes & hard-to-digest raw nuts or legumes

- Chew food thoroughly, eat slowly, and maintain good posture during and after meals

- Maintain adequate hydration- Consider adding nutritious fluids (e.g., nutrition shakes) to achieve hydration goals and meet calorie needs (inflammation increases energy and protein needs)

May benefit from19

- Including soluble, gel-forming fibers, like psyllium, which may help to slow gastric emptying, thicken stools, and support the microbiome

- Limiting insoluble fiber (wheat or oat bran, vegetable/legume peels, nuts, and seeds), which may increase the frequency of bowel movements and cause watery stool

The consumption of at least one and a half fruit servings daily may reduce the risk of developing pouchitis by increasing gut microbiota diversity.15

Key Takeaways

Fiber is not the enemy in IBD, it is an essential tool for gut health when chosen carefully. The focus should shift from restriction to personalized inclusion, adapting the type, texture, and timing of fiber to symptom patterns and disease activity.

It is always advisable to consult a healthcare provider or a registered dietitian for personalized recommendations tailored to your unique needs. Remember, everyone's experience with IBD is unique, and finding the right foods for your body is central to managing this condition effectively.

References

- Institute of Medicine: Dietary, functional, and total fiber. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy,Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol,Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients).Washington, DC: National Academies Press,2005; pp 339 – 421.

- Bischoff SC, Bager P, Escher J, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2023; 42(3):352-379. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2022.12.004.

- Chan LN (editor-in-chief). ASPEN Adult Nutrition Support Core Curriculum. 4th edition. 2025. ISBN: 978-1-889622-58-3.

- Gill SK, Rossi M, Bajka B, et al. Dietary fibre in gastrointestinal health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 18(2):101-116. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00375-4.

- Gold S, Park S, Katz J, et al. The evolving guidelines on fiber intake for patients with inflammatory bowel disease; from exclusion to texture modification. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2025; 27(1):23. doi: 10.1007/s11894-025-00975-7.

- Roth B, Al-Shareef D, Ohlsson B. Intake of fiber and micronutrients in patients with IBS. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2025; 60(10):1011-1022. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2025.2535721.

- Haskey N, Gold SL, Faith JJ, et al. To fiber or not to fiber in IBD: the swinging pendulum of fiber supplementation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients. 2023; 15(5):1080. doi: 10.3390/nu15051080.

- Whelan K, Murrells T, Morgan M, et al. Food-related quality of life is impaired in inflammatory bowel disease and associated with reduced intake of key nutrients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021; 113(4):832-844. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa395.

- Svolos V, Gordon H, Lomer MCE, et al. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation consensus on dietary management of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2025 Sep 28;19(9):jjaf122. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaf122.

- Fritsch J, Garces L, Quintero MA, et al. Low-fat, high-fiber diet reduces markers of inflammation and dysbiosis and improves quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 19(6):1189-1199.e30. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.026.

- Mortera SL, Marzano V, Rapisarda F, et al. Metaproteomics reveals diet-induced changes in gut microbiome function according to Crohn’s disease location. Microbiome. 2024;12:217. doi: 10.1186/s40168-024-01927-5.

- Haskey N, Estaki M, Ye J, et al. A Mediterranean diet pattern improves intestinal inflammation concomitant with reshaping of the bacteriome in ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2023; 17(10):1569-1578. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad073.

- So D, Gibson PR, Muir JG, et al. Dietary fibers and IBS: translating functional characteristics to clinical value in the era of personalised medicine. Gut. 2021; 70(12):2383-2394. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324891.

- McKeown NM, Fahey Jr GC, Slavin J, et al. Fibre intake for optimal health: how can healthcare professionals support people to reach dietary recommendations? BMJ. 2022; 378:e054370. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2020-054370.

- Godny L, Maharshak N, Reshef L, et al. Fruit consumption is associated with alterations in microbial composition and lower rates of pouchitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2019; 13(10):1265-1272. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz053.

- Whelan K, Ford AC, Burton-Murray H, et al. Dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome: considerations, challenges, and solutions. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024; 9(12):1147-1161. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(24)00238-3.

- Staudacher HM, Costas-Balle C, Phillips M, et al. Dietary modifications in patients with non-inflammatory bowel disease diarrhoea: a summary of the evidence and practical considerations. Frontline Gastroenterology. 2025. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2024-102855.

- Dimidi E, van der Schoot A, Barrett K, et al. British Dietetic Association guidelines for the dietary management of chronic constipation in adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2025; 38(5):e70133. doi: 10.1111/jhn.70133.

- Wall E. Nutrition therapies for patients with an ileoanal pouch: a moving target? Practical Gastro. 2024; 48(4). Available on: https://practicalgastro.com/2024/07/19/nutrition-therapies-for-patients-with-an-ileoanal-pouch-a-moving-target/

- Singh P, Tuck C, Gibson PR, et al. The role of food in the treatment of bowel disorders: focus on irritable bowel syndrome and functional constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022; 117(6):947-957. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001767.

- Gautam Naik R, Purcell SA, Gold SL, et al. From evidence to practice: a narrative framework for integrating the Mediterranean diet into inflammatory bowel disease management. Nutrients. 2025; 17(3):470. doi: 10.3390/nu17030470.

Donate

Donate