Copied

Food: The Main Course for Digestive Health 2025 Highlights

Discover what’s new and interesting in nutrition research and clinical pearls for managing common gastrointestinal conditions.

In August 2025, Nutritional Therapy for IBD attended virtually the 2025 edition of FOOD: The Main Course to Digestive Health Conference hosted by the University of Michigan Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Here are some key takeaways from the conference on the role of diet and nutrition for managing common gastrointestinal conditions, including IBS and overlapping conditions, functional dyspepsia, gastroparesis, and the mast cell activation syndrome/postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome/hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome triad.

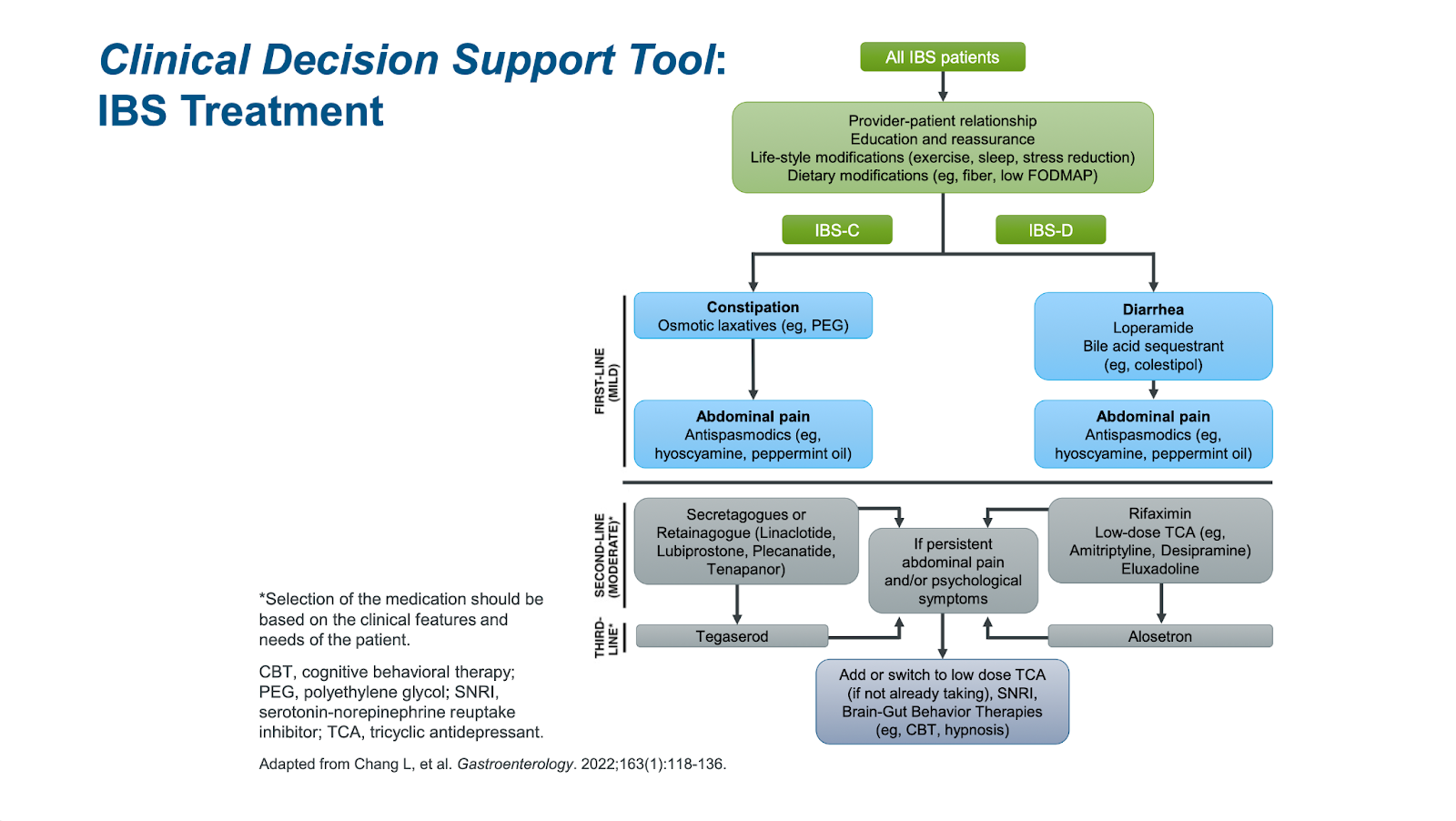

From Treating Symptoms to Understanding Causes and Choosing the Right Treatment

The current goal of medical treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is to treat symptoms. However, multiple causes of IBS co-exist, and there is a ceiling effect in terms of how well drugs work because most of the time, we have no idea which mechanisms we are treating. Prof. William D Chey, PhD, MD, from the University of Michigan, discussed available empiric therapies for IBS based on the most likely cause of burdensome symptoms, including enteric-coated peppermint oil to improve mild-moderate global IBS symptoms.1,2,3

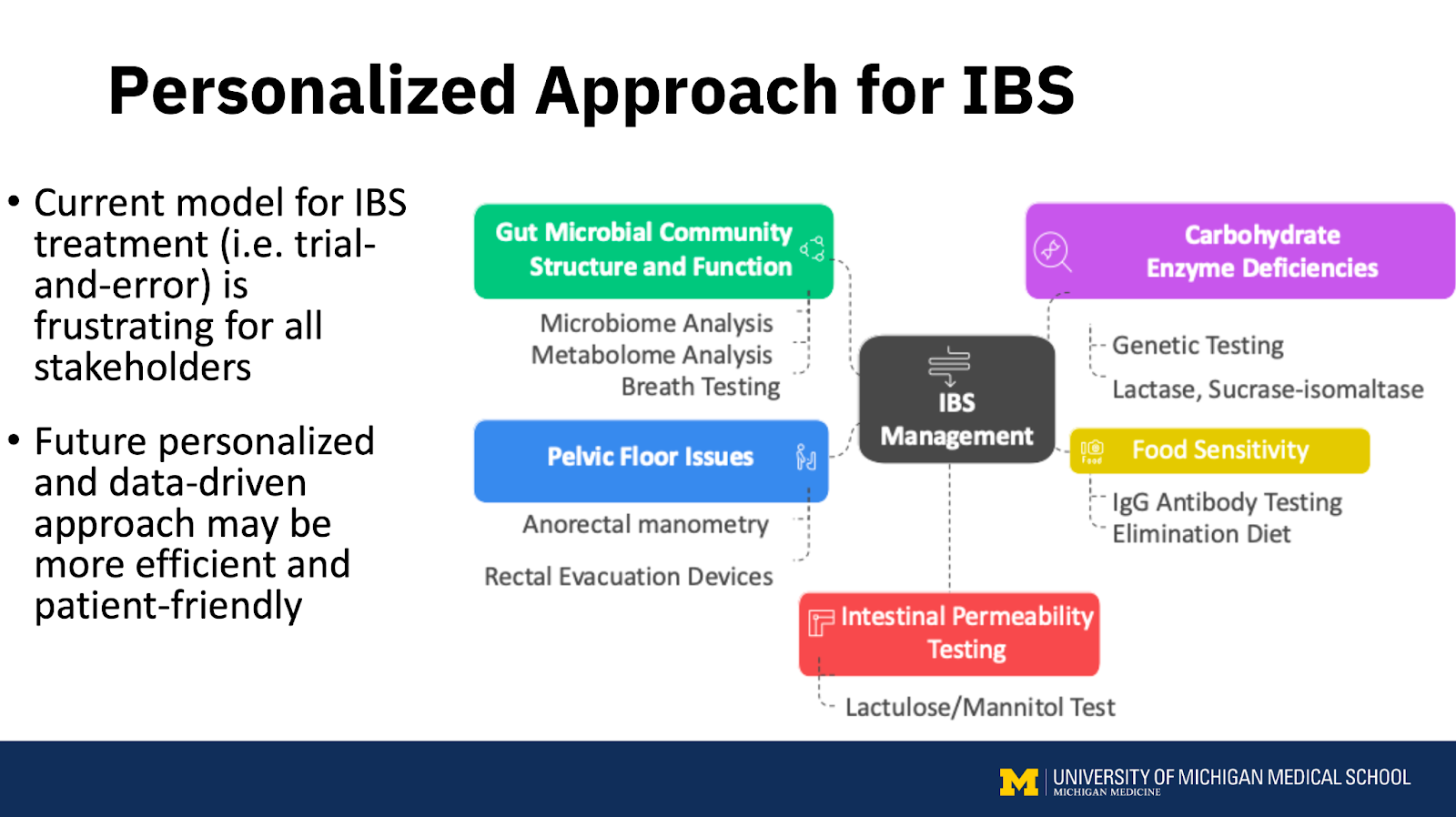

While the current model for IBS treatment, based on trial-and-error, is frustrating for both patients and providers, Allen Lee, PhD, MD, MS, from the University of Michigan, acknowledged that the way forward is to use biomarkers to subgroup patients with IBS based on symptoms and altered pathophysiology. This personalized approach for IBS may be more efficient to choose the right treatment for the right patient.

Prashant Singh, PhD, MD, from the University of Michigan, recommended determining whether the condition is truly IBS with diarrhea or another underlying issue. In some cases, symptoms may be due to organic causes arising in the gut mucosa (inflammatory bowel disease, microscopic colitis, celiac disease, eosinophilic disorders, mast cell disorders) or the intestinal lumen (bile acid malabsorption, disaccharidase deficiency, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth or intestinal methane overgrowth).

Tamara Duker Freuman, MS, RDN, CDN, practitioner at New York Gastroenterology Associates, got into various causes of constipation, including pelvic floor dysfunction that affects 40% of people with chronic constipation. Considering pelvic floor dysfunction is important when constipation fails to improve with dietary changes, supplements, or prescription medications. She notes that many patients struggle with a high stool burden, even with normal daily movements, which is the most common cause of chronic bloating complaints.

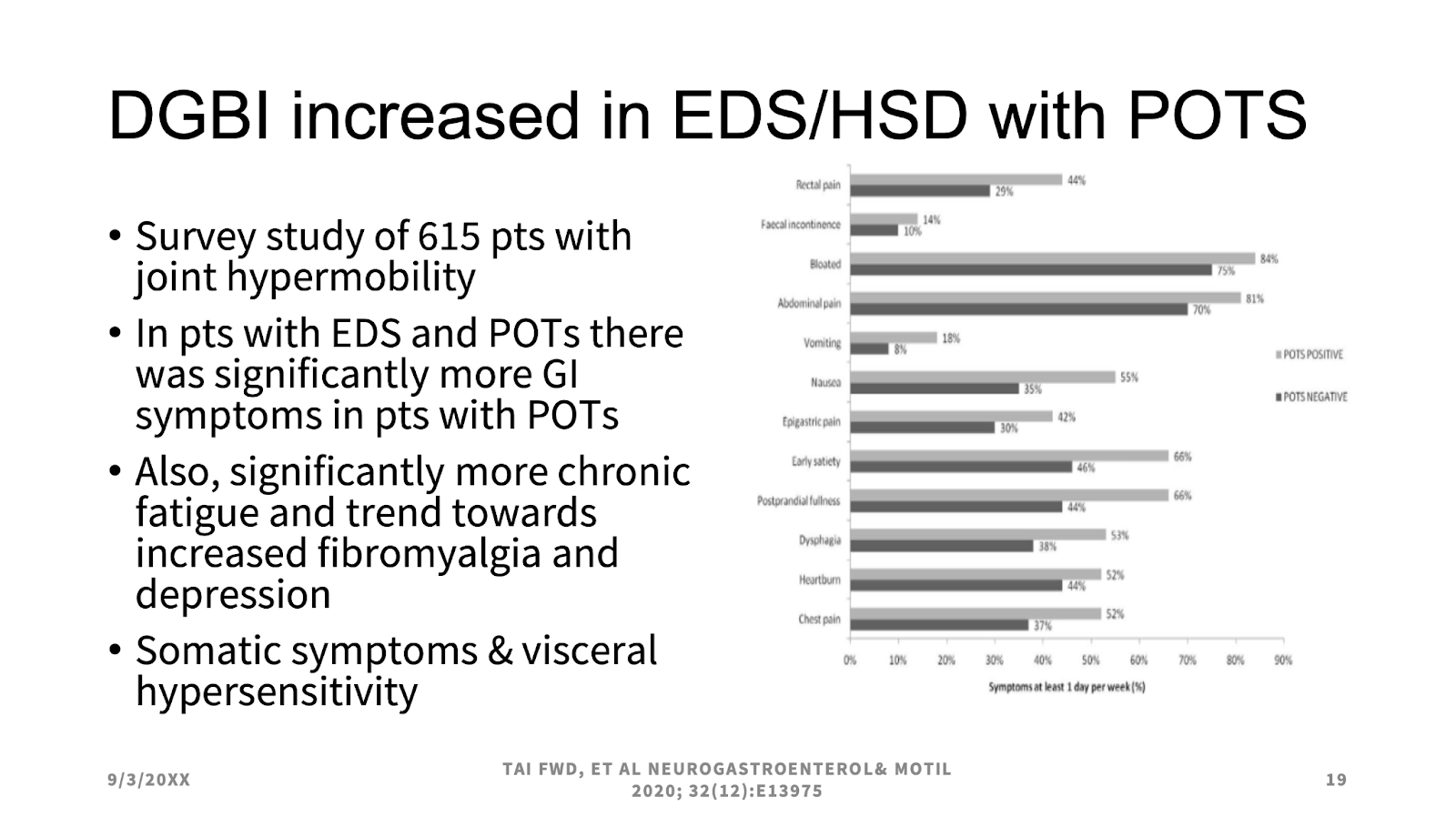

Lucinda Harris, MS, MD, FACP, FAGA, MACG, from the Mayo Clinic, acknowledged that differential diagnoses of IBS should include mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and/or hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (hEDS) (AKA “the Triad”). Family history and physical exam (Beighton scale) will diagnose hEDS, which can cause many gastrointestinal symptoms alongside hyperflexible joints, hyperelastic skin, and tissue fragility. POTS may occur secondary to EDS, while the relationship between POTS and EDS remains unclear. MCAS is theorized to be the root cause of a significant percentage of POTS and hEDS, but the relationship is controversial. Individuals with hypermobility spectrum disorders (HSDs) and hEDS who also experience IBS symptoms may have a higher psychological burden and worse quality of life. They are also more likely to experience challenges with eating or food intolerances.4

Which Therapeutic Diets and Supplements are Effective at Managing IBS Symptoms and the MCAS, POTS, and EDS Triad?

A detailed, hypothesis-driven diet and symptom recall is an essential tool for registered dietitians in selecting the most appropriate dietary intervention. Duker explained that evidence-based diets for IBS include a fiber-modified diet, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) diet guidelines, and the low FODMAP diet/’gentle’ FODMAP diet. For instance, the low FODMAP diet may be most effective when the baseline diet is high in overall or specific FODMAPs, and the patient has indicated partial benefit from other eliminations (gluten/dairy), or suspects certain high FODMAP foods trigger symptoms, and when the gas burden is high.

Diets under investigation for IBS are the Mediterranean diet, the low nickel diet, and the low histamine diet. While emerging findings suggest that some IBS symptoms are caused by localized immune system response to allergenic foods via non-IgE mediated reactions and gut barrier defects, it is too early to use elimination diets guided by food IgG panels for managing IBS symptoms.5

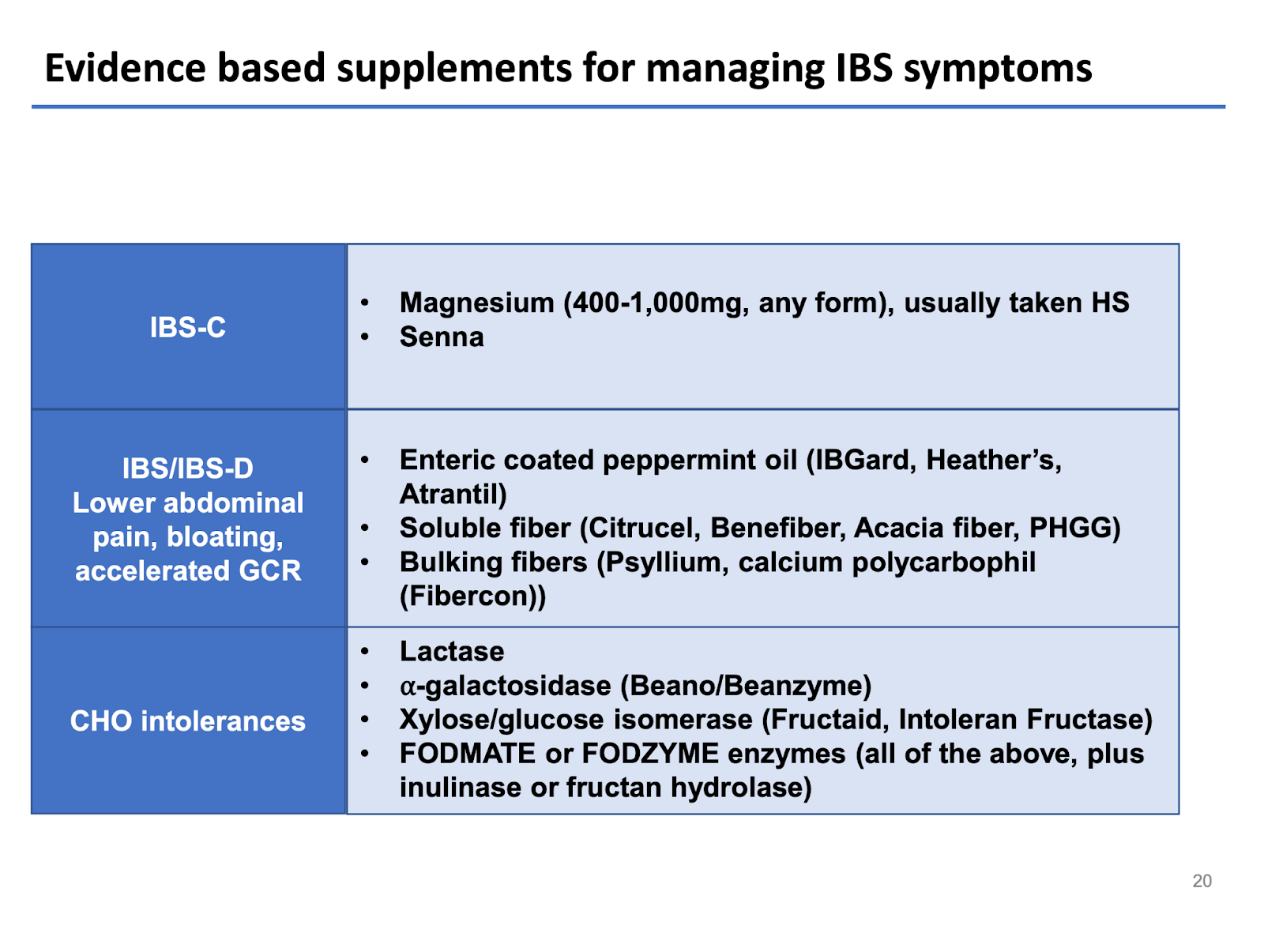

Fiber is not the enemy in IBS, and as a general rule, the most universally tolerated types of fiber are soluble fiber-predominant and low FODMAP. Patients with diarrhea or bowel urgency may do best when skewing fiber intake to soluble-rich foods (e.g., beans, oats, peas, avocado, sweet potato, pears, turnips, psyllium) and limiting intake of insoluble fiber-rich foods (whole wheat flour, wheat bran, cauliflower, green beans). Other evidence-based supplements worth trying for managing IBS symptoms based on etiology are summarized below.6

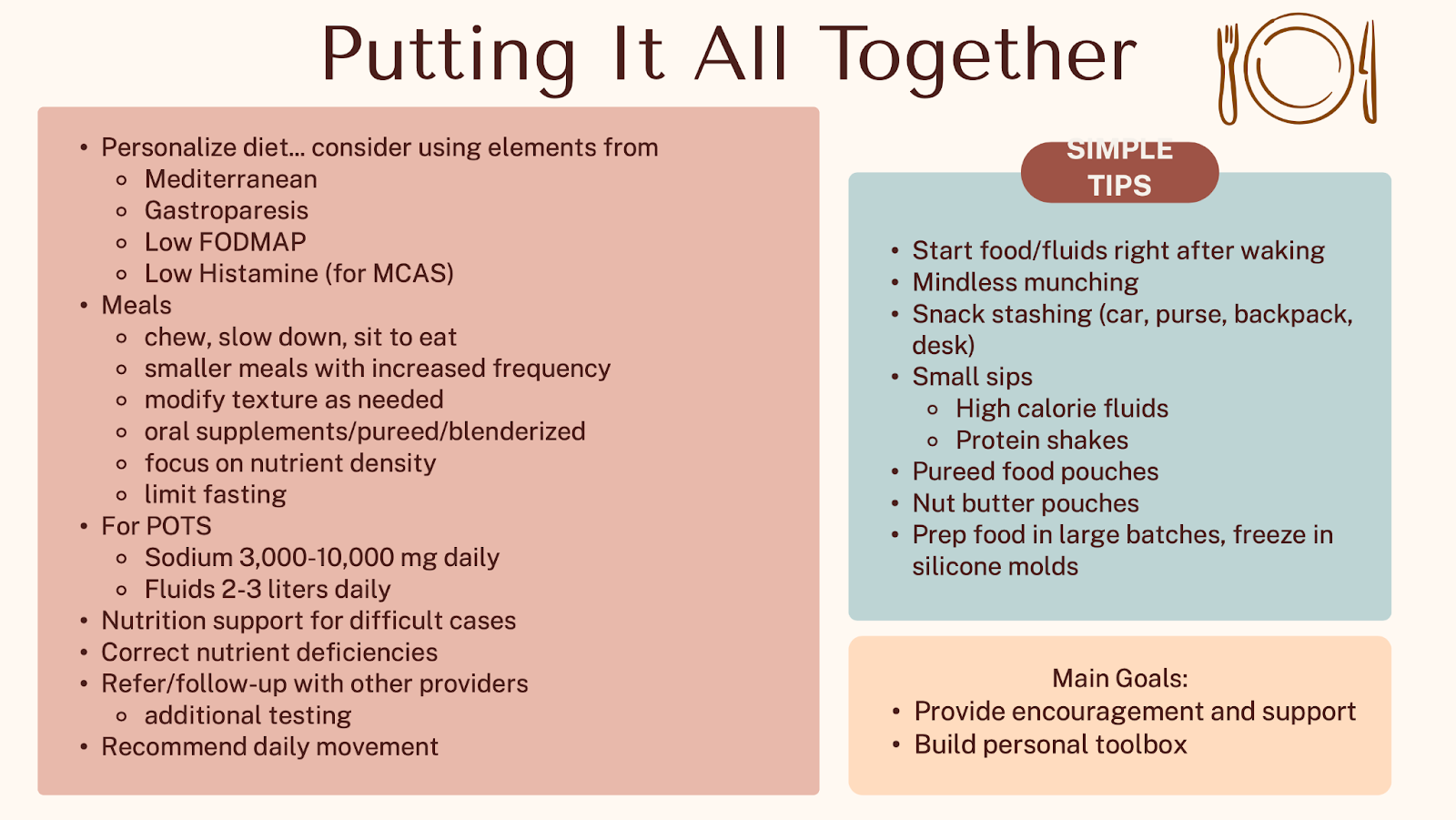

Niki Strealy, RDN, LD, owner of Strategic Nutrition, LLC, explained that dietary treatment strategies for POTS and hEDS include hydration, exercise, compression garments, and medications for symptom relief, as well as an integrative approach with multiple specialties. It is recommended to focus on increasing sodium intake (3-10 g of salt/day consumed in divided doses) and fluid intake (2-3 liters per day) to support blood volume and improve orthostatic tolerance as well as modifying meal consistency and frequency (e.g., 6-8 small, higher sodium meals) and weigh the removal of specific foods that migh trigger GI symptoms. The recently released AGA clinical practice update covers 16 best practice recommendations for the evaluation and management of patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) and hEDS or HSDs with coexisting POTS and/or MCAS.7

The majority of patients with EDS, POTS, and MCAS have tried at least one complementary and alternative medicine modality due to their desperation for symptom relief, with magnesium being one of the most commonly used supplements.8 Food supplements that have been tested at least in one study in patients with dysautonomia and hypermobility syndromes include vitamin C, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and folate (methylfolate).9,10 Although there is a rationale for using fiber/prebiotics and probiotics, no evidence supports their use in patients with HSD/hEDS.

Non-dietary means for managing IBS symptoms are also worth trying. Simone Peters, PhD, psychophysiologist and founder of the Mind + Gut Clinic, delved into clinical evidence of GI behavioral therapies for IBS, including gut-directed hypnotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, and mindfulness and stress reduction Apps. A team-based, collaborative, and multidisciplinary approach to care, integrating GI specialists, registered dietitians, and psychologists in a single virtual model, is likely the most effective way to reduce healthcare costs, improve outcomes, and support patients with complex or high-severity IBS.

Is it Functional Dyspepsia or Gastroparesis? A Guide to Similarities and Differences, Causes, and Dietary mManagement Tips

Fullness after eating, early satiation, epigastric pain or burning, upper abdominal bloating, nausea, and vomiting may have their roots in functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis, which are two common conditions that have overlapping symptoms and may often co-exist (30-40% of patients may switch diagnoses over time).11 Functional dyspepsia includes symptoms of “bad digestion” in the absence of an identifiable structural or biochemical cause, while gastroparesis is a delay in gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction.12

Anthony Lembo, PhD, MD, from Cleveland Clinic, explained that emerging evidence showed that there is a strong association between functional dyspepsia and a previous gastrointestinal infection, with other mechanisms involving an impaired gastric accommodation, visceral hypersensitivity, and increased duodenal eosinophils. On the other hand, gastroparesis is associated with significant delays in gastric emptying, impaired stomach accommodation, damage to the vagal nerve (common in diabetes mellitus), low-grade inflammation, and a loss of interstitial cells of Cajal, which regulate smooth muscle contractions.

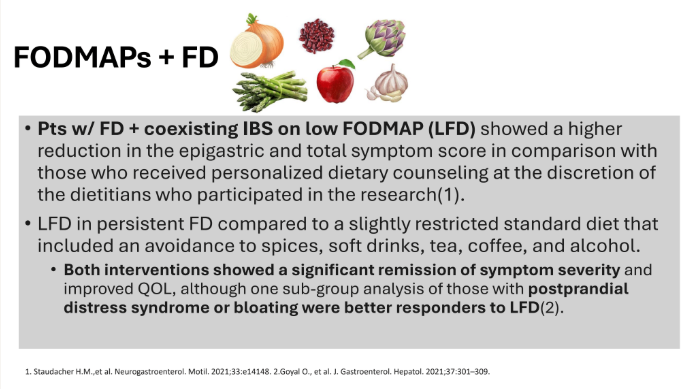

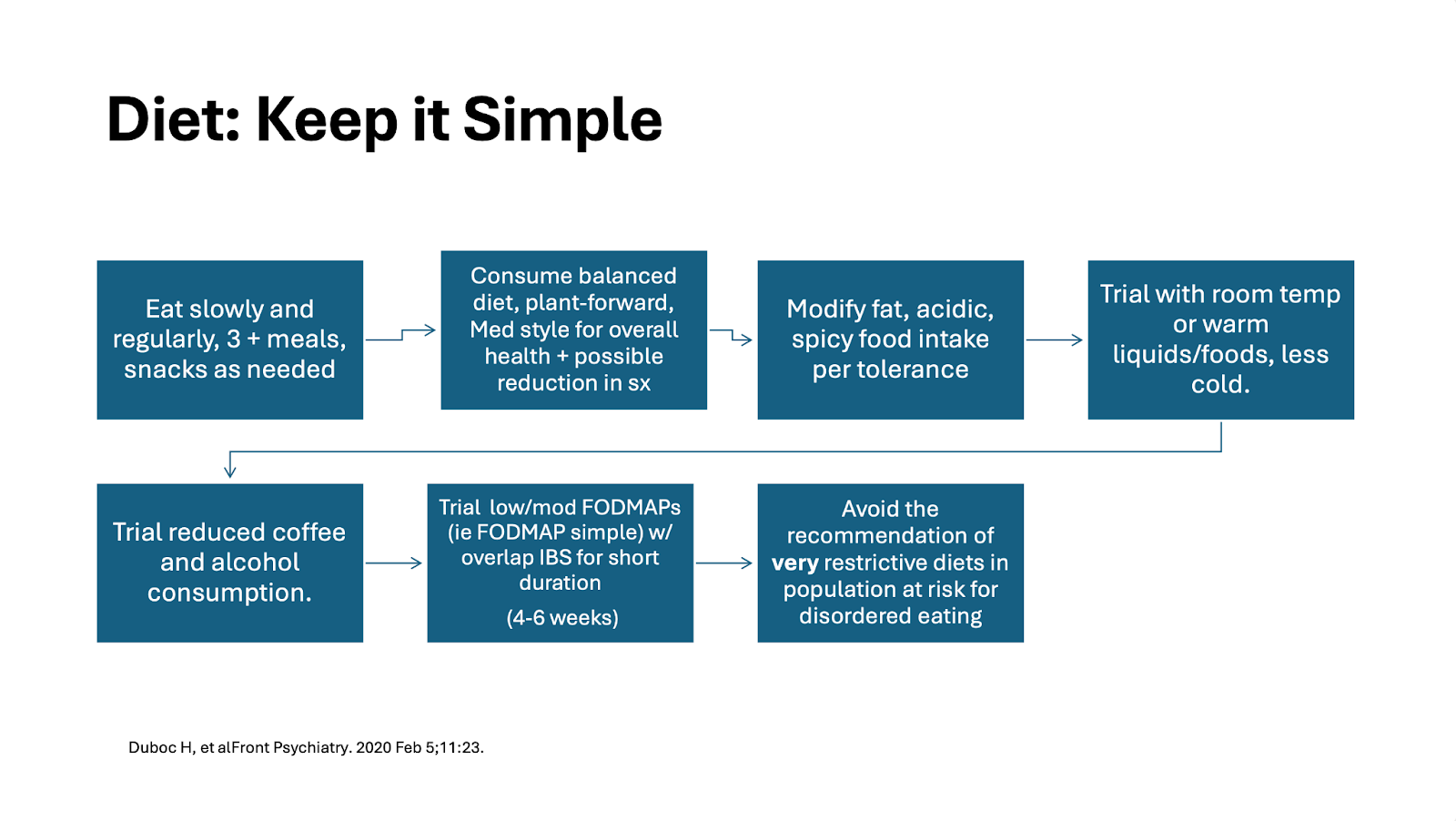

Kate Scarlata, MPH, RDN, GI expert dietitian with 30+ years of digestive health experience, acknowledged that the role of food in functional dyspepsia is complicated, with a significant influence of patients’ expectations and beliefs around foods (e.g., in patients with functional dyspepsia, symptoms can be exacerbated not only by the ingestion of fat-rich foods but also by a meal that the patient perceived high in fat). Although few dietary intervention trials have been conducted for functional dyspepsia, one study found the low FODMAP diet was comparable to a slightly restricted standard diet that included an avoidance to spices, soft drinks, tea, coffee, and alcohol in patients with functional dyspepsia.13 The fact that symptom triggers vary widely among individuals supports that dietary strategies should be tailored based on patient history, symptom patterns, and tolerance.14 Beyond whole food diets, some herbal supplements, including peppermint and caraway oil blend, artichoke leaf extract, and chios mastic gum, may improve symptoms and quality of life in patients with functional dyspepsia.15,16,17

When it comes to gastroparesis, the four key components to a diet approach include: 1) eating smaller meals, 2) particle size of food (a diet with small particle size is recommended), 3) spreading fiber intake across the day and changing its form (cooked and blended work best), and 4) spread high fat foods over the course of meals and snacks while keeping the portions amounts in checked as per individual tolerance.18

Eating behaviours also matter in motility disorders and DGBI, as 10-80% of patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction showed avoidant/restrictive food intake disorders.19 While exclusion diets and food restrictions may benefit symptom management in some patients, healthcare providers should first screen for maladaptive dietary behaviors across all patients requiring special diets. When appropriate, nutritional therapies should be offered in conjunction with a gastrointestinal-expert registered dietitian. A referral to mental health providers is recommended for patients at risk for eating disorders and disordered eating.20

Nuances in Nutrition Care for Ostomies and Short Bowel Syndrome

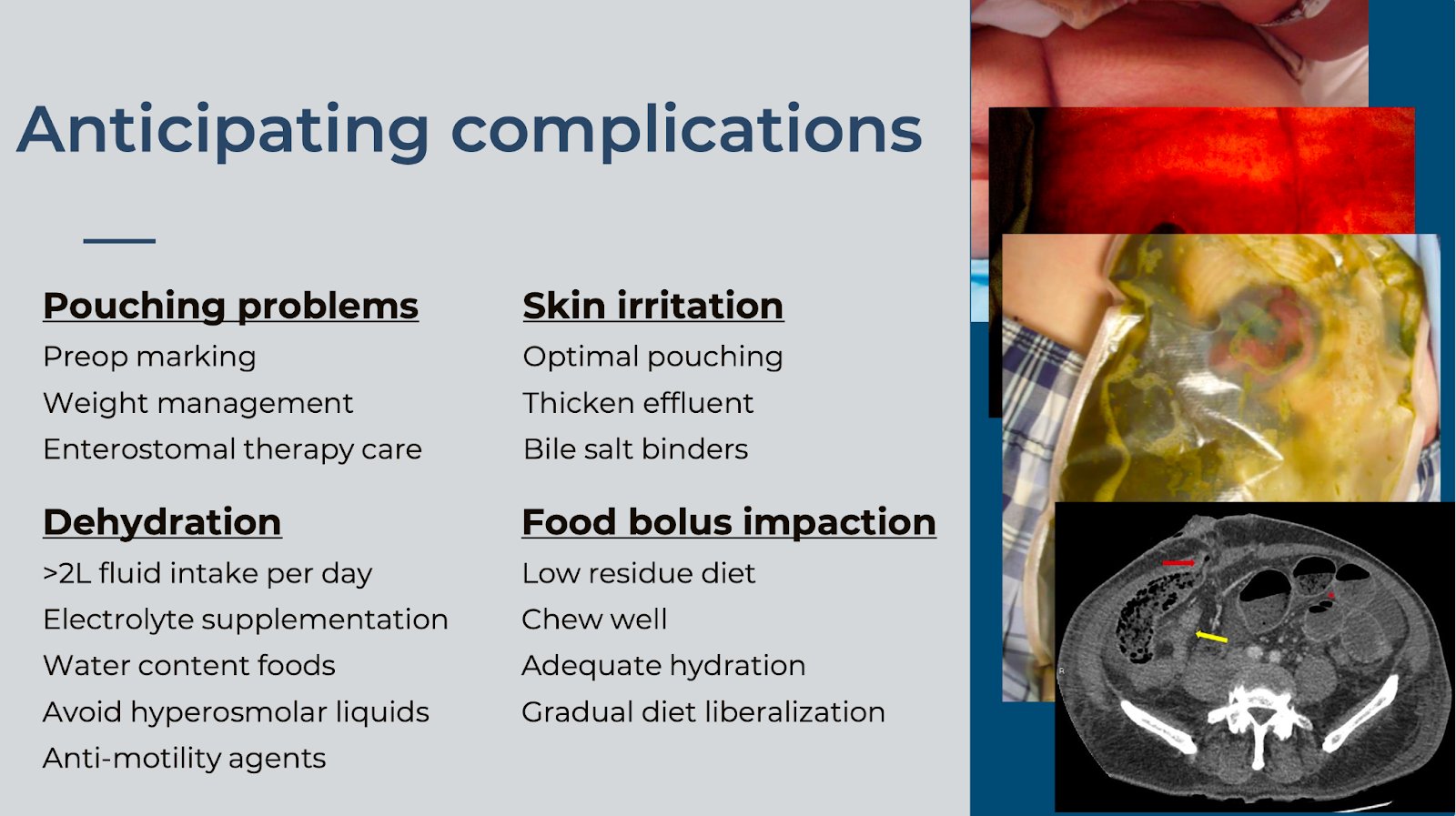

Ostomies are common in the management of patients with gastrointestinal conditions, including colorectal cancer, IBD, diverticular disease, and intestinal perforation. Common complications that the registered dietitian needs to be aware of include pouching problems, skin irritation, dehydration, and food impactions. Scott Regenbogen, MD, MPH, from the University of Michigan Health, acknowledged that adequate stomal care and nutrition support improve clinical outcomes and reduce hospitalizations, and provided advice for anticipating complications.

Laura Manning, MPH, RDN, from Mount Sinai Hospital, highlighted that a multidisciplinary approach is optimal for better ostomy care and managing complications and should involve a specialized nurse, a social worker, a GI psychologist, a pharmacist, and a GI registered dietitian. Nutrition matters beyond the immediate perioperative period, and Manning provided some practical dietetic advice before and after surgery (read more):

- Nutrition before surgery aims to improve patients’ metabolic reserves, reduce muscle loss, facilitate quicker recovery, and minimize post-operative complications. It includes:21,22

- Screen, assess, diagnose, and correct malnutrition

- Participate and counsel patients on prehabilitation nutrition 6-8 weeks before surgery and the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol

- Oral Nutrition Supplements containing immune-enhancing nutrients

- Carbohydrate loading: a preoperative beverage containing more than 50 g of carbohydrates improves post-operative insulin resistance, reduces length of stay, and enhances patient comfort

- Nutrition after surgery aims to reduce complications, length of stay, and enhance recovery. It includes:22

- Early post-operative feeding

- Increased calorie and protein needs

- Moderation in high-fat foods (fried, heavy sauces)

- Modify textures (small particle size diet): peel and cook vegetables to fork/tender soups, peel fruits, and choose soft, tender meats (meatballs, meatloaf, stews)

- Small, frequent meals

- Slow reintroduction of foods

- GI soft diet plus Oral Nutrition Supplements of low osmolarity

- Instructions for hydration needs: Oral Rehydration Solutions between meals (sips) are preferred over concentrated sweets (juices)

- For outpatients, it can take a few weeks for stoma swelling to decrease and output to adapt to 6-8 empties per day

Carol Rees, MS, RDN, GI nutrition support specialist, shared tips and tricks for nutritional recovery and gut adaptation in short bowel syndrome (SBS), defined as the physical or functional loss of small bowel such that a patient is unable to maintain nutrition, hydration, and electrolyte status while consuming a normal diet and fluid intake. SBS is also defined as < 200 cm or > 75% of working small bowel lost.23 Potential causes of SBS in adults are complications from abdominal surgery, malignancy, mesenteric ischemia, Crohn’s disease, and trauma.24

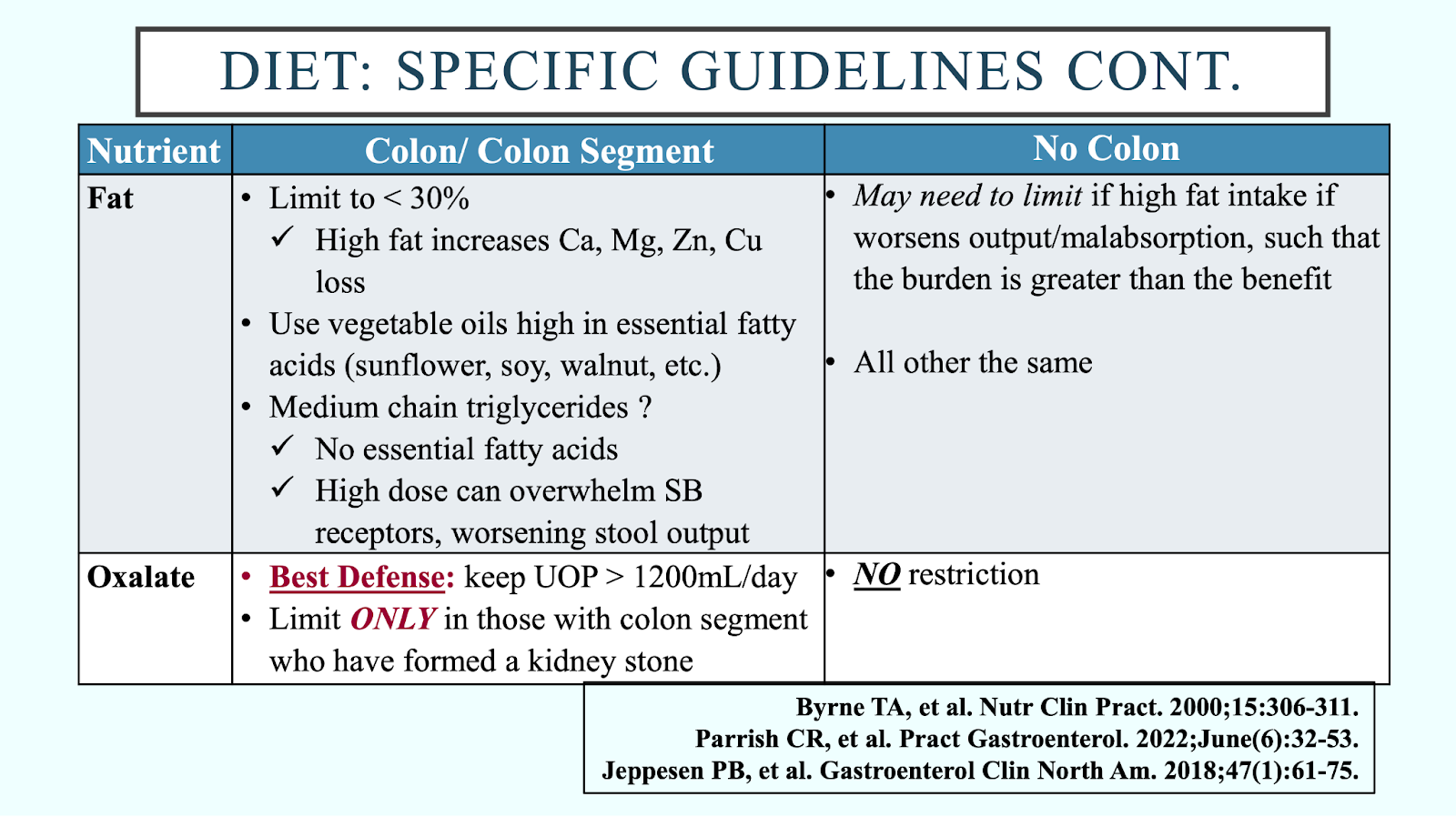

SBS can manifest in the form of diarrhea, nutrient malabsorption, bile acid diarrhea, bacterial overgrowth, kidney stones, and gallstones. Understanding the patient’s remaining GI anatomy will help the dietitian tailor the diet. The SBS diet is quite similar for those with and without a colon, with important differences acknowledged below (see “Diet: specific guidelines”). When it comes to hydration, isotonic beverages (oral rehydration solutions) are recommended, and hypertonic fluids (e.g., fruit juices, sodas, sweetened drinks of any kind, and commercial liquid nutritional supplements) should be avoided as they pull more water into the small bowel lumen. Equally as important is to teach the patient how to drink; the majority of fluid intake should come from sipping all day long between meals, as fluids are more efficiently absorbed this way.

There are insufficient data to support fiber bulking agents, probiotics, and glutamine, while complete vitamin/mineral supplements (chewable, crushed, or liquid) can be considered in some patients. When choosing medications, it is important to consider their contribution to increasing water in the small bowel and fluid volume to take all medications. Also, it is important to bear in mind that some excipients in liquids, elixirs, and suspensions (e.g., sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol) can make diarrhea worse and should be avoided, as well as delayed-release formulas.25

Further reading:

From treating symptoms to understanding causes and then choosing the right treatment:

- Chey WD, Hashash JG, Manning L, et al. AGA clinical practice update on the role of diet in irritable bowel syndrome: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2022; 162(6):1737-1745. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.248.

- Chang L, Sultan S, Lembo A, et al. AGA clinical practice guideline on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Gastroenterology. 2022; 163(1):118-136. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.016.

- Lacy BE, Pimentel M, Brenner DM, et al. ACG clinical guideline: management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021; 116(1):17-44. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036.

- Choudhary A, Fikree A, Ruffle JK, et al. A machine learning approach to stratify patients with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome/hypermobility spectrum disorders according to disorders of gut brain interaction, comorbidities and quality of life. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2025; 37(1):e14957. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14957.

Which therapeutic diets and supplements are effective at managing IBS symptoms?

- Singh P, Chey WD, Takakura W, et al. A novel, IBS-specific IgG ELISA-based elimination diet in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, sham-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2025; 168(6):1128-1136. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.01.223.

- Duker Freuman T. The bloated belly whisperer. St Martin’s Press: 2018.

- Aziz Q, Harris LA, Goodman BP, et al. AGA clinical practice update on GI manifestations and autonomic or immune dysfunction in hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025; 23(8):1291-1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2025.02.015.

- Doyle TA, Halverson CME. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a qualitative study. Front Med. 2022; 9:1056438. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1056438.

- Do T, Diamond S, Green C, et al. Nutritional implications of patients with dysautonomia and hypermobility syndromes. Curr Nutr Rep. 2021; 10(4):324-333. doi: 10.1007/s13668-021-00373-1.

- Courseault J, Kingry C, Morrison V, et al. Folate-dependent hypermobility syndrome: a proposed mechanism and diagnosis. Heliyon. 2023; 9(4):e15387. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15387.

Is it functional dyspepsia or gastroparesis? A guide to similarities and differences, causes, and dietary management tips

- Huang IH, Schol J, Khatun R, et al. Worldwide prevalence and burden of gastroparesis-like symptoms as defined by the United European Gastroenterology (UEG) and European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM) consensus on gastroparesis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022; 10(8):888-897. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12289.

- Keszthelyi K. Functional dyspepsia or gastroparesis? A guide to assessment, investigation and management. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2025; 16:392-400. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2024-103011.

- Ashoorion V, Hosseinian SZ, Rezaei N, et al. Effect of dietary patterns on functional dyspepsia in adults: a systematic review. J Health Popul Nutr. 2025; 44(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s41043-025-00884-5.

- Goyal O, Nohria S, Batta S, et al. Low fermentable, oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols diet versus traditional dietary advice for functional dyspepsia: a randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 37(2):301-309. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15694.

- Heiran A, Bagheri Lankarani K, Bradley R, et al. Efficacy of herbal treatments for functional dyspepsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Phytother Res. 2022;36(2):686-704. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7333.

- Li J, Lv L, Zhang J, et al. A combination of peppermint oil and caraway oil for the treatment of functional dyspepsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019; 7654947. doi: 10.1155/2019/7654947.

- Dabos KJ, Sfika E, Vlatta LJ, et al. Is Chios mastic gum effective in the treatment of functional dyspepsia? A prospective randomised double-blind placebo controlled trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010; 127(2):205-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.11.021.

- Liu JJ, Doerfler B, Cline M, et al. The management of gastroparesis symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025; 120(10):2213-2219. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000003341.

- Mikhael-Moussa H, Bertrand V, Lejeune E, et al. The association of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and neurogastroenterology disorders (including disorders of gut-brain interaction [DGBI]): a scoping review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2025; 37(9):e70039. doi: 10.1111/nmo.70039.

- Scarlata K, Zickgraf HF, Satherley RM, et al. A call to action: unraveling the nuance of adapted eating behaviors in individuals with gastrointestinal conditions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025; 23(6):893-901.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.11.010.

Nuances in nutrition care for ostomies and short bowel syndrome

- Berkel AEM, Bongers BC, Kotte H, et al. Effects of community-based exercise prehabilitation for patients scheduled for colorectal surgery with high risk for postoperative complications: results of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2022; 275(2):e299-e306. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004702.

- Greco M, Capretti G, Beretta L, et al. Enhanced recovery program in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg. 2014; 38(6):1531-41. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2416-8.

- Iyer K, DiBaise JK, Rubio-Tapia A. AGA clinical practice update on management of short bowel syndrome: expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022; 20(10):2185-2194.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.032.

- Parrish CR, DiBaise JK. Managing the adult patient with short bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017; 13(10):600-608.

- Kumpf VJ, Parrish CR. The clinician’s toolkit for the adult short bowel patient part II: pharmacologic interventions. Pract Gastroenterol. 2022; (7):12-31.

Stay Informed of the Latest News in Nutrition and IBD

Support our Mission

Your donation will help us to enhance the well-being and health outcomes of patients with GI conditions.

Donate Donate

Donate